Rival Fur and Provision Posts on the Saskatchewan, 1792 - 1800

In 1792, the principal fur trade rivals on the North Saskatchewan River — the Montreal-based North West Company and the London-based Hudson's Bay Company — extended their competition for furs and provisions westward into what is now Alberta. Side by side, a few kilometres below modern Elk Point, they established Fort George (NWC) and Buckingham House (HBC). For the next eight years they traded metal goods, textiles, arms, ammunition, rum and tobacco for the coveted furs, especially beaver, supplied by indigenous peoples. The main fur suppliers were the Cree and Assiniboine who hunted in the woodlands north of and the parklands south of the river.

Both companies needed large quantities of meat and fat to make pemmican, a concentrated food that nourished the men of the canoe brigades on their long, gruelling journeys to and from the Great Lakes and the Hudson Bay.

The main source of pemmican was the great herds of bison hunted mainly by the Blackfoot tribes in the grassland and parkland to the south of the forts. Both forts were not only productive fur trading posts; they were also key provision posts which annually supplied tons of pemmican for use throughout the northwest.

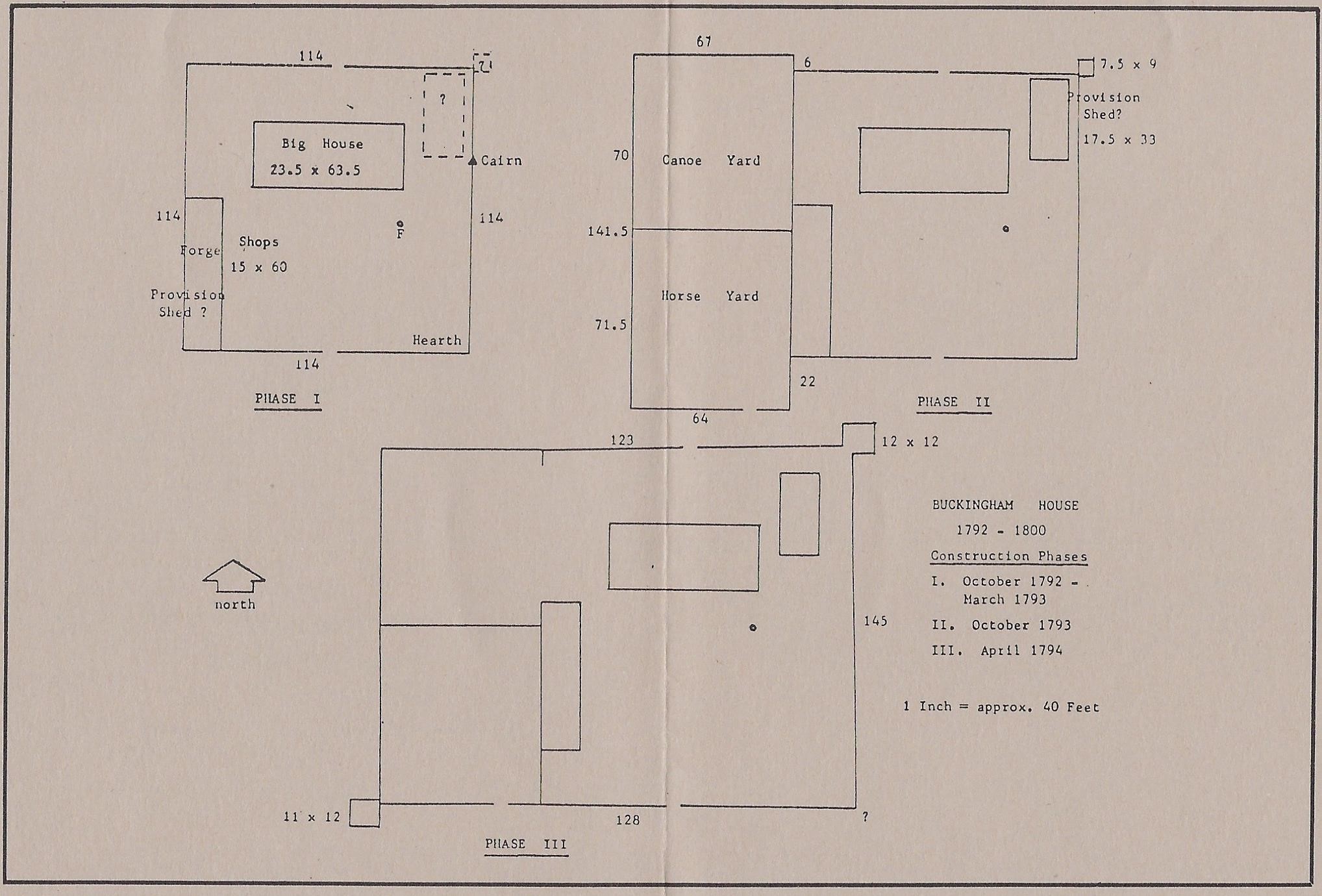

BUCKINGHAM HOUSE 1792 - 1800

Construction Phases

- October 1792 - March 1793

- October 1793

- April 1794

At Fort George in 1792, NWC partner Angus Shaw was in charge of about sixty men, mostly Canadians from Quebec, many of whom had indigenous wives and mixed- blood children. At neighboring Buckingham House, Inland Chief, William Tomison, supervised thirty-eight men, all but four of them Orkneymen like himself.

Living quarters at both establishments were terribly cramped for the men and their families. Officers, Shaw and Tomison, enjoyed more spacious quarters. Each post had fur and meat warehouses, a blacksmith shop, an ice house, a trade shop, and a trade goods store, all surrounded by a high stockade with corner bastions or blockhouses. These defences were vital. In 1793 and 1794 the Fall (Gros Ventre) Indians attacked four posts in the Saskatchewan district and burned one of them to the ground.

Always the underdog in manpower and supplies, the HBC at Buckingham House was lucky to trade half the quantity of furs and provisions traded by the NWC at Fort George. Though trade rivalry was keen, the two forts cooperated when danger threatened and shared a water supply from a well located between them. The successes at these two forts in large measure dictated the fortunes of the parent companies in London and Montreal for the short but crucial span of five years. But at the inland posts, five years could be construed in some instances as a sign of longevity. By 1800 fur resources of the immediate area were nearing exhaustion and both companies abandoned the site in favor of others further upstream on the North Saskatchewan River.

As of 2024, it was 232 years ago that the twin forts battled on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River for predominance in the western fur trade.

There is now no visible remnant of the presence of two large fortified wooden fur trade posts. Yet the first meter of soil is littered with the fragments of that early and highly specialized society as well as the outlines of the buildings and encampment that were erected there.

In 1976, when the province of Alberta recognized the significance of the Fort George and Buckingham House, the fort sites were designated as a Provincial Historic Resource.

Long before the Province's direct involvement, the people of the Elk Point area knew about the site and its historical significance. In large measure, the survival of the site and the continued preservation of the resources for later research programs is due to the concern of local historic preservation advocates.

The Fort sites have since been the subject of intensive archaeological and historical research projects. The findings of these projects confirmed the importance of the site, and led to the development of the Fort George and Buckingham House Provincial Interpretive Centre.