By WM. C. BARTLETT

IN SIX PARTS-PART III

THE next day was a busy one. The lake with its reported bounteous supply of fish was what attracted us most just then; the problem was how to secure some of them. The moss was so dense along shore that a pole was out of the question; we could not reach open water with a line that way. At last, Bill, assisted by the Professor, hit upon a scheme: They would build a raft, and as lumber seemed to be very scarce In the vicinity, It was decided, 'after much pondering’, to build it out of logs.

Leaving me in camp to shoo away the bears and other native citizens, and in the meantime, boil a pot of beans, they grasped their axes and with about ten pounds of spikes brought along for just such an emergency, they swung away down the lake to where was situated the heavy timber best suited to their purpose.

The forenoon waned, and my beans had intermittently simmered, boiled over on the fire, and laid down on me entirely; and I heard throughout this time the steady pat, pat, of the axes, ringing clear, from the heavy timber below. The noon hour came, the beans were done and dinner ready for three; but the axes were still going; slower now. with occasional pauses as it to rest. The afternoon was drawing to a close and the hot sun low in the West, when the sound of the axes ceased, and for half an hour the stillness of a lifeless solitude hung over the lower end of the lake; then—wonder of wonders! What Is that familiar sound I hear? Oars in oar locks? Never! It cannot be! For where in this unknown place would one get a pair of oars, much less a boat in which they could be used?

I sprang to a point where my eyes would verity my ears, and there, sure enough, I observed, coming up the lake, with rapid bounds, a brand new, regular skiff, the little bow wave falling away, white, from the stem, and bubbly wake training out behind, straight as one of the pines that lined the shore. Bill handled the oars; I knew his stroke although too far to know the man; that long, low recover and noiseless dip, would discover him to me in any place on earth. The Professor sat humped in the stern.

As the boat drew near, I stood on the bank above, waiting, with all kind of feelings of pleasure and curiosity as to how they had managed such a miracle as a skiff on Long Lake, and of course expected to see some sign of elation on their part, but I didn’t. Instead they slowly and stiffly got out, pulled her nose upon the gravelly beach with a vicious jerk, savagely tied her fast, then, giving her a parting kick, climbed soberly up the bank to the tent.

I ventured a curious question, but Bill ripped out something that sounded like, "Oh go to hell, any beans left?” and as I thought I recognized the word beans in the exclamation I ventured no more, but went and got the pot of beans, some bread, bacon and coffee, and placed It before them. After everything had been devoured and they had rubbed salve on their blistered hands, the pipes were lit and I heard what It was all about.

After leaving camp in the morning they had repaired to the heavy timber, from whence I had heard the sound of their axes, and proceeded to clear about an acre of land, the trees thereof to be used In the construction of the raft. They had then cut the trees into suitable length and after laboriously rolling them to the water’s edge, they spiked and lashed them together In the required form. This done, they cut two long poles to be used in propelling their stately craft, then, everything thing ready, pried her off the shelving into deep water, where she Immediately sank.

Then came the interval of quiet I had noticed, when they sat on the reed-fringed shore and sadly gazed on the symmetrical mass of heavy balm logs, peacefully reposing on the bottom of the crystal lake. And thus they sat, pondering on the inability of man to foresee his shattered idols, the disappointments In life, and the uncertainty of reward for ambitious energy expended until a vagrant breeze, freighted with the fragrant aroma of pork and beans was wafted down from the camp above, and, assailing their hungry nostrils, wakened them with a start from the reverie Into which they had fallen.

Gathering up their axes, they cast one last look at the result of their labors, then started campward by way of a short cut across the mouth of the little creek, before mentioned. Parting the bushes at the edge of the creek, they pushed through preparatory to wading across, when, "Ye gods and little fishes!!” What Is this they see rocking placidly in the little waves cast up by the sinking raft—a skiff? Yes, a genuine new yellow pine skiff, oars and all, and as Bill said in concluding his story, "The ‘dun’ thing lay there all day, within fifteen feet of us, and never said a word."

Ducks were not so numerous on Long Lake as on those south of the river. Still, there were a good many, mostly black duck, and blue wing teal, with a sprinkling of mallard, red head and widgeon, while, as on all the lakes of this duck paradise, the black, chicken-coot, fairly swarmed along the moss-covered areas close in shore. At the south end of the lake the water was very shallow for a long distance from the shore, and was grown up so densely with the water rush that a boat could only with difficulty be forced through.

Bill had been sitting out on the edge of the bank smoking and watching the evening flight of duck, which were settling in this watery jungle, and getting duck hungry, proposed that we take the new boat and bring down a couple of brace for breakfast.

I got my pump gun—the only shotgun in the outfit—and together we rowed down to where the ducks were congregating, leaving the Professor to tend camp. By the time we had forced the boat far enough into the thick growth to be entirely hidden, the sun was sliding' from view behind the hills to the West, and the ducks were coming In in clouds and dropping with a rushing roar Into the reeds on all sides. Standing in the stern of the boat I waited for the proper duck, and the proper shot. A flock of green wing teal—one of the midgets of the duck tribe—passed with a whistling rush of air not five feet over our heads, and swift as a flight of arrows, passed from view. Blue wing teal, the most unwary of ducks, sailed in on set wing and dropped with a splash, sometimes, not ten feet from our boat. Black duck and widgeon hurtled across the sky, whipped once, then settled; and still I waited. Suddenly I heard Bill, who sat facing me, exclaim, "Look out, here they come!" and turning I saw a flock of noble mallard, wings set and yellow legs hanging, dropping like bullets from high up in the air, and coining straight for the boat.

I waited until the old emerald headed leader was within twenty feet of me, then I turned, and, picking two young drakes out of the now wildly towering flock, I dropped them with two clean shots then handed the gun to Bill for his turn. There was a moment of silence. Then the echoing shots crashed back two-fold from the wooded shore, and reverberating like distant thunder, rolled away up the enclosing slopes, to die with a final muffled roar.

Pandemonium now reigned supreme in local duckdom. With a roar of a thousand wings, and led by the old timers that knew too well the spiteful crack of the shot gun. the ducks rose enmasse from the rushes, and with hysterical quacking, surged here and there in a panic of wild fright. Mallard and rod head, black duck and teal, uncertain of the source of the dreadful sound, flashed close overhead, gave one startled glance downward, then, with squawks of mortal fright, mounted straight up on wildly beating, terror driven, wings. Mongrel grebe rose to the surface close along side the boat, and disappeared in a flash of spray for a longer dive to safety. and the black coot swarmed out past us. treading water, and making for the open lake, like the horniest duck devil of them all was close behind.

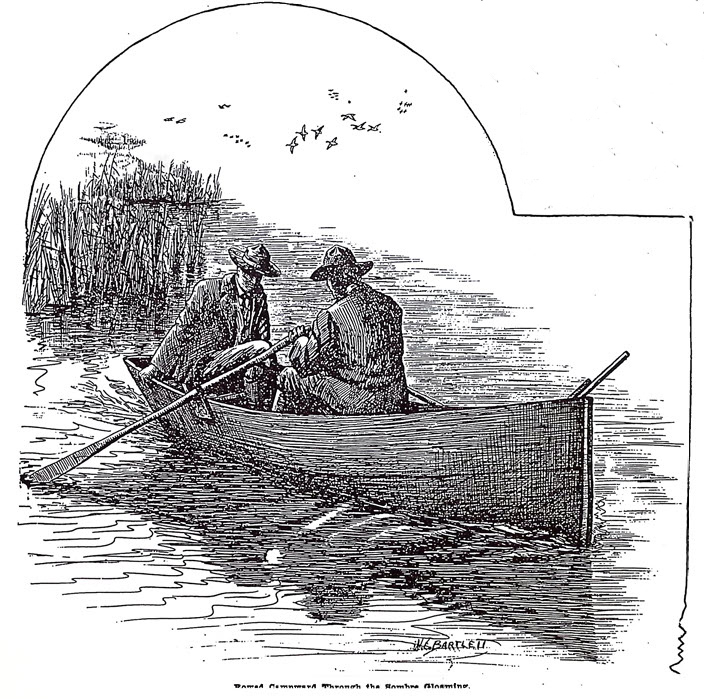

Bill brought down a brace of young green heads to add to those I had already killed. then after watching the flight for a while, we forced the boat through to where our ducks lay, picked them up and then rowed campward through the sombre gloaming of the approaching night. Our second day on the lake was one long to be remembered. About 10 o'clock a fierce wind—gradually grown stronger since morning—came seething down from the north, lashing the lake into soapy froth, and howling through the timber like a thousand demons let loose out of Hades. Our tent, setting out in the open, received the full force of the screeching blast. and we were kept busy tightening guys and bracing poles against Its persistent force. In vain, for at last, along in the afternoon, a fiercer gust than usual caught us unawares and over went the tent with a great clattering of tinware, to lay as it fell until the wind subsided enough to allow it being set up again.

Bill and the Professor had planned to spend the day trolling for pickerel, but the coming of the wind made it Impossible, until later, when the wind subsided enough to make trolling practical. Then, getting out their tackle, they repaired to the boat and went diligently to work In an effort to lure the five pounders from their watery haunts; but nary a lure “went” with the fish of Long Lake. They were too well fed at this season of the year to want to eat their spinning tinware. After an. hour or so of persistent trolling the fishermen gave it up without a strike and returned to camp and supper of bacon, duck, dough-god and coffee.

While Bill and the Professor were fishing. I killed a couple of blue wing teal, and they were hanging, unplucked on a nearby poplar limb when they returned. The Professor spied them at once and entered a protest against my wasting ammunition on mud hens, and would not be convinced that they were one of the most toothsome little ducks that fly. But we were getting used to the Professor now, and his opinions did not prevent Bill and myself from doing ample justice to the little fowls after they had been well broiled over the coals.

The Professor was the greatest fellow to argue, and the most exasperating of any fellow I had over been thrown in contact with on any expedition or enterprise. He was so contentions that be was comical, but you never though to laugh until the incident of which he was the principal had become history. If a pot of beans was boiled he must have then "Boston baked" and would proceed to run them over the fire in an attempt to make them so, until they resembled black oblong bullets: then he would eat them all himself to prove that they were the genuine article. He declared that he bad always been used to hot biscuits for breakfast and could not get along without them in camp. If you baked a dough-god of flour, water and baking powder, he declared it "rank" and must have "flap-jacks" or corn-pone.

And so on. down the list, he argued, condemned, found fault and contended until one day Bill, to stop a heated argument as to whether they should fish or shoot ducks, thew him out of the boat into the lake and he came ashore through the slimy moss, and for a day or so after was so taken up with pouting that he forgot to contend and we had a brief period of peace.

The next day dawned clear and warm, without a trace of the over-fresh breeze of the day before. We were up early as we intended to build up the bottom of the tent with logs that we might have more room on the inside. We were busily engaged at this task when a horseman rode up to the tent. Upon our invitation he dismounted and introduced himself as Mr. Deisel, from about two miles up lake, where he had built a cabin. He was a trapper and hunter by vocation, and had driven all the way from Oklahoma in a "prairie schooner,” accompanied by his wife and three small children. He cleared up the mystery of the new trail across the creek, at the lower end of the lake by which we had reached our camp, also that of the finding of the new skiff, for he had made them both himself.

The Trapper (as we will know him from now on) Informed us that moose, elk and deer were very plentiful, and that there were a few bear, but their range was principally about three or four miles up the lake and to the north. Upon being informed that this was what we were after, he, In true southern style, Invited us to move our camp up near his cabin, and generously offered to drive down with his wagon and move our outfit if we would come. We readily accepted and by noon we were loaded and on the way to our new location.

By a faint trail, which led diagonally up the face of the steep slope that everywhere rim'd round the lake, we reached the comparatively level ground above, then turning north, we drove for about two miles through the thick willow and poplar brush and "at last came out In a level space of grass covered prairie wherein was located the Trapper's new spruce-log cabin.

Selecting a suitable set for our camp. Out near the brush where wood was handy, we soon had our tent up, also one loaned by the accommodating Trapper, set up tor sleeping quarters, near by. That evening, after supper, when the campfire was going nicely, the Trapper joined us and sat far into the night detailing, in an interesting manner, his past experience with trap and rifle. Imparting many valuable hints as to the proper way of taking various kinds of big game he had encountered in his eventful life and outlining plans for a moose hunt the next day.

It seemed that since his arrival, the moose and black-tall deer, which were then plentiful in the Immediate neighborhood of his cabin, had retired to the mountains proper, about two miles farther north. It was there he proposed that we seek them on the morrow.

You can download the original photocopy here:

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Bartlett William C Hunting and Camping in the Alberta Wilderness 3 1910 Searchable.pdf | 1.37 MB |