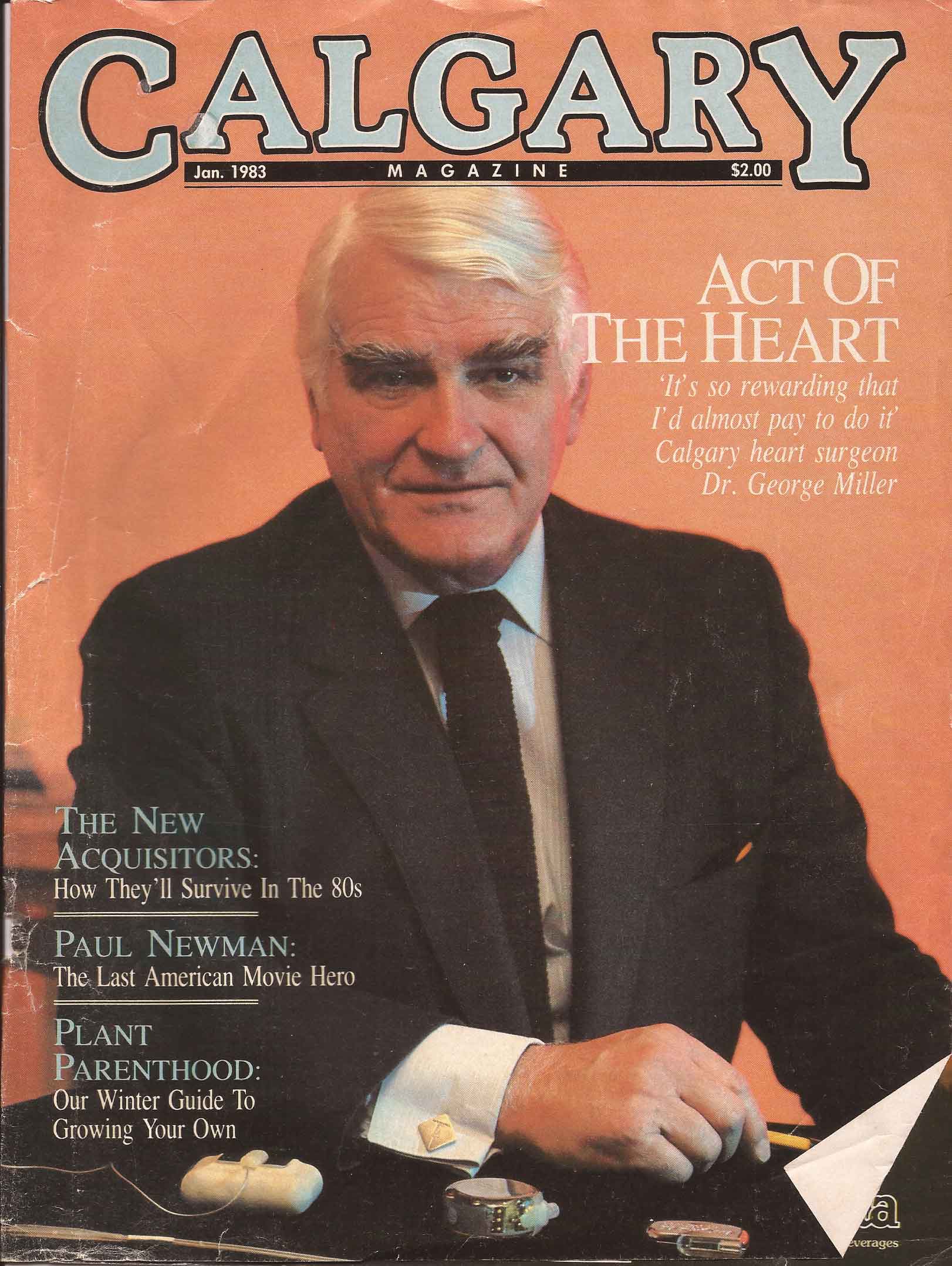

Act of the Heart: A day in the life of cardiac surgeon George Miller

Photo Essay by Chris Thomas

January 1983

FOR YOUNG GEORGE Miller, in Elk Point, Alta., the journey had already begun. As an adventurous 4-year-old in the small hospital his father and an associate had built, he knew well enough how to escape the notice of scurrying adults. When the coast was clear he would carefully pull the doors ajar and peer through the crack to watch his father perform surgery while his mother administered anesthetic.

Today George Miller is chief surgeon and founder of the Southern Alberta Cardio-Vascular Centre at Holy Cross Hospital. He also performs operations at Foothills and Colonel Belcher hospitals. His boyish enthusiasm for surgery is undiminished; his colleagues praise his energy and skill. To say that he is well-liked and respected is an understatement.

In the intervening years, Miller received his medical degree at University of Alberta. He joined the army in 1942 and served until 1947. Returning to Elk Point upon his discharge, Miller practised for a year with his father before moving to Saskatoon for a year of post-graduate work in pathology.

With surgical training still ahead of him, Miller arrived on the doorstep of the Mayo Clinic in 1950. As luck would have it, he was placed on the service of Dr. John Kirkin, a pioneer in, and the world's leading authority on, open-heart surgical techniques.

For Miller, the excitement of this new field of surgery unfolding before him was irresistible. He spent the next six years in training and research before returning to Calgary to open his own cardiovascular unit at Holy Cross.

Those early days at Holy Cross were restricted to closed-heart surgery, which does not require a heart-lung machine since the heart continues to beat throughout the operation. Not until 1961 could the hospital afford a heart pump.

At this point, the long after-hours training sessions began. Operating on dogs in Holy Cross research labs, Miller began training his team for their roles in the latest open-heart techniques. Late in 1961, they performed their first operation, and since then the flow of patients has been ever- increasing.

From his colleagues at Stanford, Salt Lake City, Houston and the Mayo Clinic, Miller keeps abreast of the latest developments in his field. His musings on its future call for awesome progress over the next century.

For the near future he sees the organic transplant procedures almost completely replaced by the blossoming mechanical heart technology. Within 50 years, Miller suspects, genetic research will have provided clinically applicable techniques that will completely eliminate hereditary predispositions to heart disease. "At that point," he smiles, "people in my field will be just about put out of business."

Although his career has been very demanding of his personal time â he and his wife, Marilyn, have four grown children â Miller maintains medicine has broadened his life immensely. "I've been very fortunate to have a wife who understands the demands of my professional life and between us we've developed a family that has adjusted to it."

As anyone who knows George Miller will tell you, as well as being a consummate professional, he is an incredibly patient, compassionate and understanding man. Many thanks to him and his staff for allowing us to carefully pull the doors ajar and peer into his fascinating world.

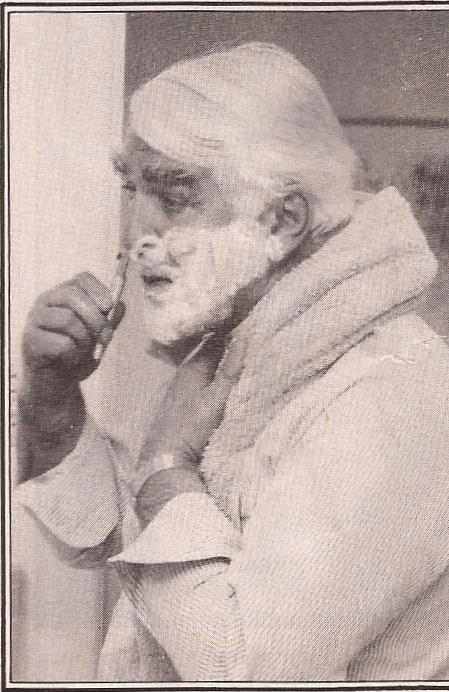

Miller starts his day with a close shave at 6 a.m. With the possibility of surgical emergencies ever-present, he is seldom certain when he will have time for his next one.

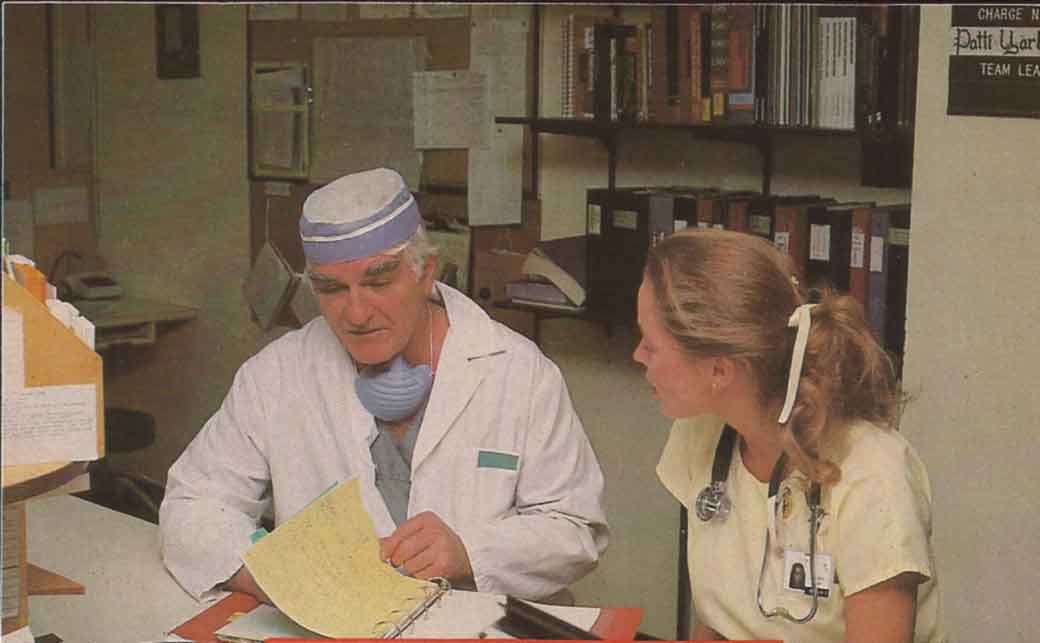

With two heart operations behind him, Dr. Miller's day is only half finished. Here he reviews patient charts with nurse Bonny Fox. A normal work day is 14 hours, but emergencies can stretch that to 48.

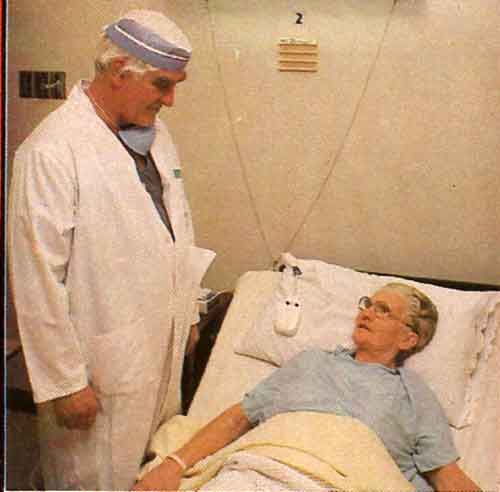

Miller makes a pre-operative visit to patient Katherine Bossert, of Wrentham, Alta. He explains that her aortic valve replacement must be temporarily postponed until her blood chemistry improves.

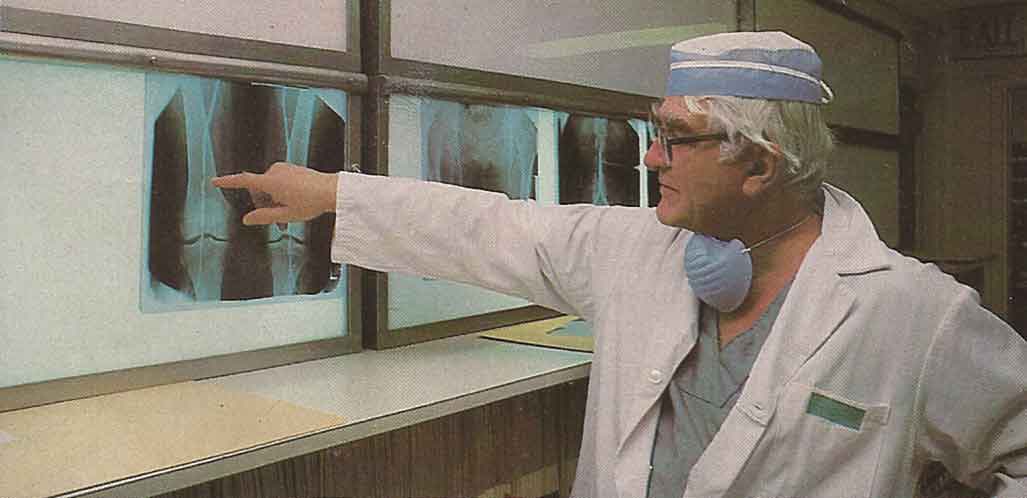

As part of his daily routine Dr. Miller stops off at the X-ray department and film-viewing room at Holy Cross to assess patients' conditions and suitability for surgery. Here he displays the effects of arteriosclerotic disease (hardening and narrowing of the arteries) in a patient's thigh. Arteriosclerotic disease is running a close race with cancer as mankind's number one killer. Although usually not evident until middle-age, it tends to become increasingly problematic, often necessitating surgery to restore proper blood flow. Miller says predisposition to this disease appears to be hereditary.

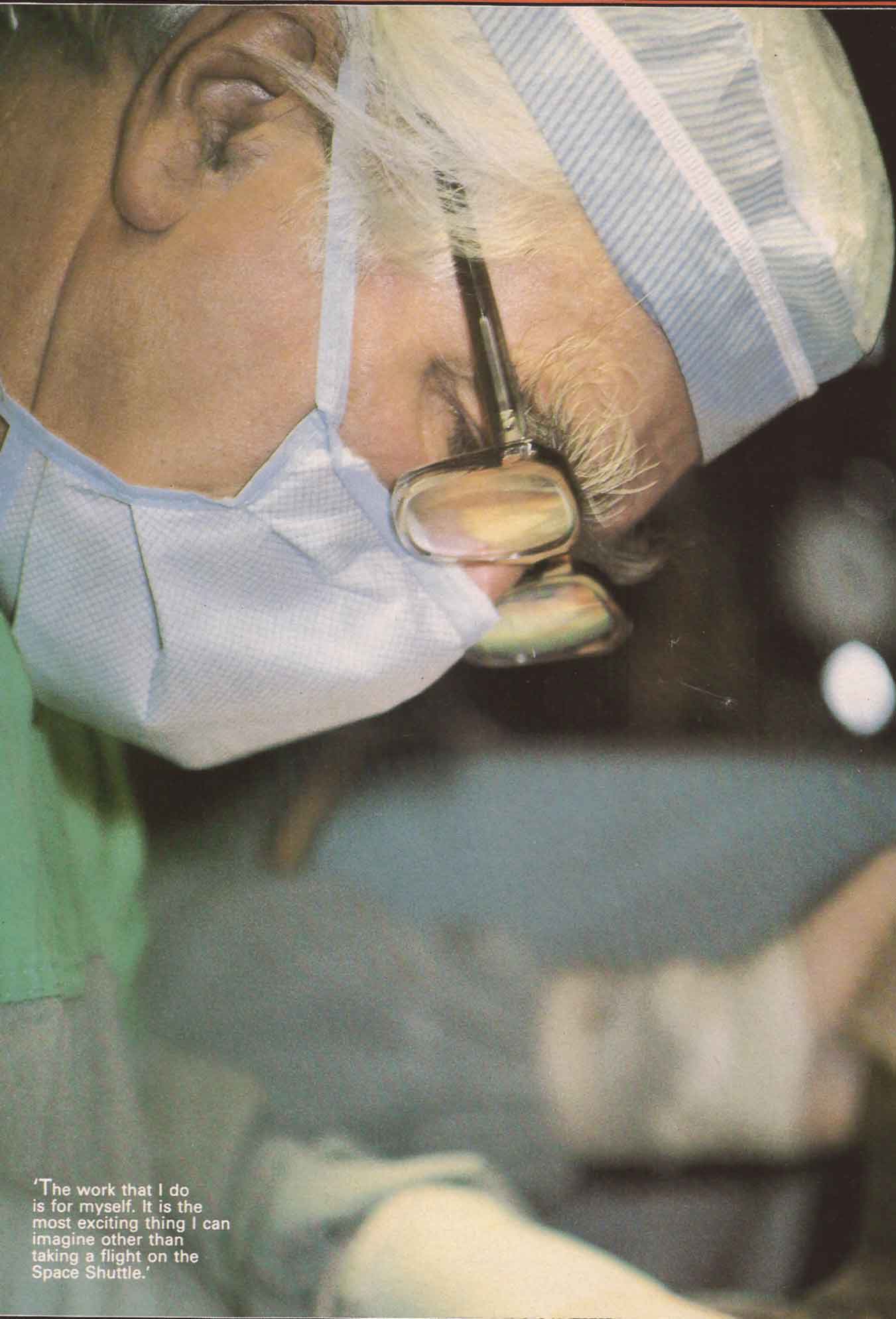

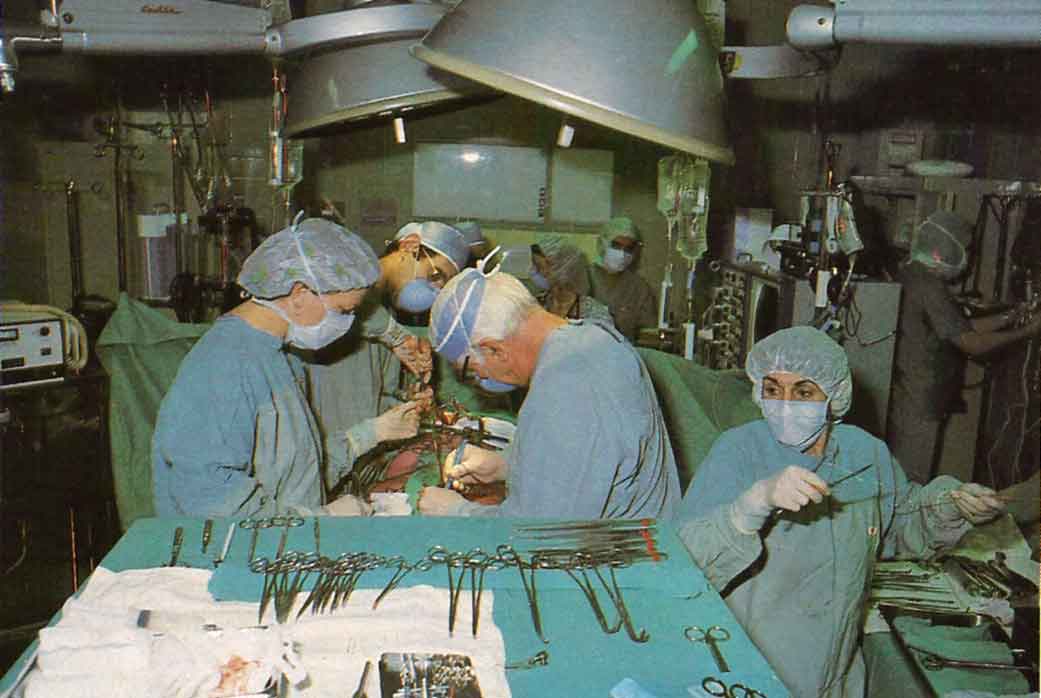

A patient suffering from arteriosclerotic disease undergoes a coronary bypass operation to restore proper blood flow to the heart muscle. Although the body's entire blood supply passes through the heart, its own supply must pass through four small arteries. If one or more of these arteries narrows, the heart's efficiency decreases and the probability of heart attack greatly increases.

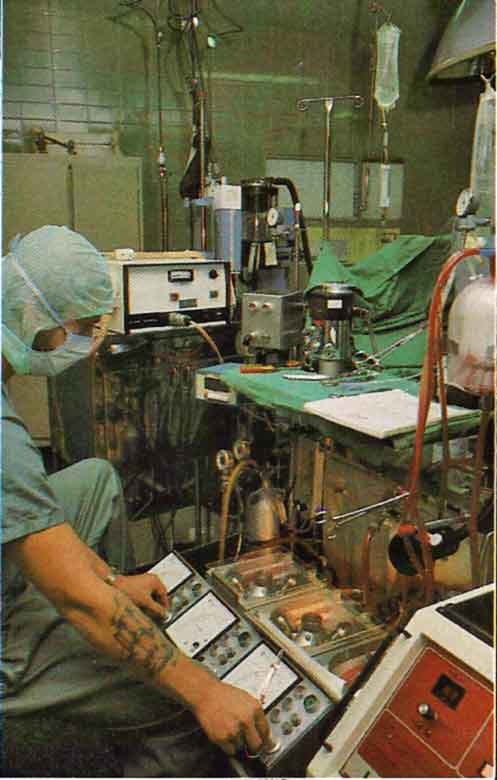

At age 31, Glen Madden has already attended to thousands of cardiac surgery

patients. As a cardio-pulmonary perfusionist, he is responsible for the

operation of this Sams heart-lung machine. This equipment oxygenates, circulates and

controls the temperature of patients' blood while heart and lungs are immobilized.

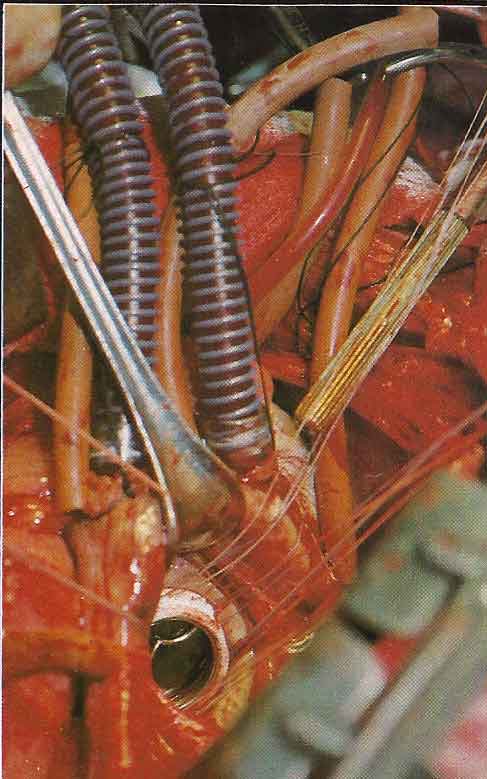

This heart's new mechanical aortic valve (in the lower section of the photograph) is in place. The tubes attached to the heart carry the body's blood to and from the heart-lung machine. Mechanical valves such as this are constructed of materials originally developed for the American space program.