IN SIX PARTS—PART V

The next day was like the preceding one, very warm for so late in the year, with a light south wind blowing; two conditions which made moose hunting impracticable. The warmth would bring out the intolerable gnats, and the moose, having to be approached from the direction from which the wind was coming, would detect our presence with their keen sense of smell long before it would be possible to see them. If we would be able to make a circuit and stalk from down the wind the least crack of a dry twig or other noise we might make In forcing a way through the brush would, owing to the extreme quiet and the acute sense of hearing possessed by all the deer family, send them trotting away with the speed of running horse long before we could approach near enough to shoot. As the Trapper declared, "We might select such a day as this and tramp down wind until we ran into the Arctic Ocean without seeing or hearing anything larger than a snowshoe rabbit."

Therefore, moose being out of the question, we loafed around the camp all forenoon, reloading shells, cooking and doing other little odd jobs necessary in camp life, and In the afternoon took the shot gun and went down on the lake for duck.

When we left Vermillion for our camp on Long Lake It was our Intention to only remain about two weeks. In view of this I had before leaving accepted an Invitation from a young business man of Vermillion to join him In a shooting and exploring trip Into the Cold Lake country, about 250 miles north. Bill and the Professor, owing to the evident abundance of game in the neighborhood of our camp, decided to stay indefinitely where they were, or at least until I returned from Cold Lake. As we had only brought provisions for a two weeks’ stay, it was of course necessary that more be obtained to meet the requirements of a longer stay than was first Intended, and that at once, before a possible cold snap should close the trail.

With this end In view, bright and early the next morning Bill and the Professor set out on a long walk to Vermillion, from where they would return with the needed supplies packed on a horse, which I In turn could ride back In time to join my friend and party on the Cold Lake expedition.

Shortly after they had swung away over the trail on the beginning of their long tramp and I was left alone, the Trapper came over from his cabin and proposed a day's sport hunting willow grouse, which were to be found nearly any place in the surrounding willows and poplar thickets. The willow, or birch, grouse is one of the North wood’s additions and a great many stories have been written about him and his silly, ungrouse-llke habits, most of which are correct.

One writer says of him that he will fly up In a low bush and accommodatingly wait for you to knock him out with a, club. I found that he was right in some cases and under certain conditions. Another writer affirms that the bird will sit quietly on a limb and allow itself to be lassoed around the neck with a little string noose on the end of a pole. He also 1b right under the same conditions. If you have a good dog that will chase him out of the brush, he will at once fly Into a nearby bush or tree and as long as the animal Is near he will allow you to take any liberties with him you wish. Ho does not care for you; he has never seen you before and will not even recognize your presence; but he has met and had some strenuous experiences with the yapping, crazy-acting beast below, only before It looked more like a coyote or fox; so he takes a tighter hold of the limb with his little feathered toes and nervously flips his long tall and stares down out of black-bead eyes Into the red mouth, yawning to receive him should he miss a limb and fall. Then you may use your club, or noose. He will take no chances with the dog. But, on the other hand, if you have no dog, about the only thing you will see of Mr. Grouse, and that only If you are very quiet and stealthy In going through the brush, will be a glimpse—only a faint glimpse—of a shadowy something—you don’t know if It Is a snowshoe rabbit or what—scuttling through the thickest part of the brush. Then, if you set out In pursuit, perhaps you will get another glimpse and a shot at random as he takes to wing and hurtles away through the brush to safety.

The Indians call him the 'fool hen” because of this abnormal fear of a dog and take full advantage of It to capture him. He is identical with our own ruffed grouse, with the exception of a slight difference in color, and will In time, as he learns his real enemy (man), develop as much or more cunning than his brother of the States.

The Trapper’s method of hunting them was, in one particular, unique and out of the ordinary. He had brought with him from the South a pair of long-eared foxhounds, such as we arc all familiar with. These he same as they would a coon or lynx, and in a very satisfactory manner until If It so chanced they should run across the trail of some game more worthy, when they would go bellowing away, out of hearing, and leave him to kick out his own grouse or return to camp, as he chose.

We had only penetrated a short distance into the brush when the hounds gave tongue and dashed away through a tangle of willows and trees about fifty yards distant in a poplar sapling. The Trapper followed on a run, yelling to the dogs at the top of his voice to quiet them and prevent them from trying to dig up, chew oft or climb the bush or sapling in which the grouse had taken refuge. I followed ns fast as possible, pushing and crowding through the jungle of undergrowth, tripping over pea vines, and in my hurry getting unmercifully lashed by malicious limbs and scratched by vicious rose briers. I now came up to where he was waiting to give me the first shot at one of the three grouse, which were nervously surveying the dogs from the branches above. Using a .22-callber rifle and shooting at the head, I killed two of them, while the third fell to a quick, well-directed shot from the Trapper’s big rifle.

From that on It was a constant scramble through the thickets to reach the clamoring dogs and the birds they had treed until at last the long-drawn, musical trail cry of the foxhound came to our ears and announced the end of the hunt for grouse. The dogs had started something more worthy of their mettle.

At first the Trapper thought It was a wolf, while I suggested a fox; but it was neither one. The wolf, when followed by the hounds, always runs straight away and out of the country. In this case they were constantly in hearing, and they way they were faulting, then baying, followed by the excited tongueing of a' view, eliminated the fox also, and told in plain hound language that they had up and going one of the most ferocious animals, for his size, In the world—the Canadian lynx.

"That shu’ Is a lynx," commented the Trapper, and putting his cupped hands to his mouth he gave a long-drawn "Who-e-e-eah” to encourage the hounds, then plunged away through the brush In the direction from which the sound of the chase came, while I, as usual, followed In his wake, pushing, crowding and scrambling through the thickets in an excited endeavor to be In at the kill.

The hounds had now dropped into a shallow coulee about a quarter of a mile ahead, and their excited tonguing had given place to a short, regular baying, which signified that the lynx had taken to a tree. Making all haste possible, I had almost reached the thick clump of spruce growing In the bottom of the coulee where the lynx had come to bay, when there was a howl of pain from one of the dogs, a shot, then bedlam let loose again.

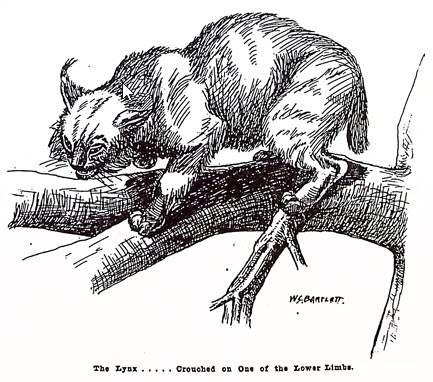

The lynx had leaped from the tree at the approach of the Trapper and landing among the dogs had nearly put one of them out of the chase, then bounded away, followed by a snapshot from the Trapper’s rifle and closely pressed by the hounds. Taking a course down the rocky bed of a nearly dry creek, which wound through the bottom of the coulee, the lynx ran for about 100 yards, giving me an Ineffectual shot as he passed below, and again took refuge from his pursuers In a large balm tree growing on the bank. The Trapper and I reached the spot at about the same time. Cautiously pushing through the dense, tangled mass of undergrowth which surrounded the lynx’s retreat, we advanced to where we could get a sight at his feline majesty.

He was crouched on one of the larger limbs, his large, wicked yellow eyes flashing like live coals, tufted ears flat along his big, round, catlike head, and his powerful legs gathered under his body, ready for the spring which would mean a terrible battle, and perhaps death, for the brave hounds and more or less danger to ourselves. Like the generous Southern gentleman that he had always proven himself to be, the Trapper, in consideration of this being my first lynx, handed me his heavy rifle. Taking careful aim between the vicious yellow eyes, I fired, and with a rasping snarl the big cat leaped far out and fell at our feet, dead.

By the time that we had secured his beautiful, though hardly prime, skin the sun was getting low and as we had over a mile and a halt of tedious brush to push through in order to reach camp, we shouldered our rifles and, calling the hounds to heel, returned to camp, well satisfied with the day’s exciting sport.

Bright and fair, with a fresh wind blowing straight down from the Arctic Ocean, the next day was an Ideal one for moose hunting in the hills to the north, and It did not take the Trapper and myself long to decide to take advantage of these weather conditions. The night before had turned still and cold

and the white frost still lay on the trail, when, at 8 o’clock, after a substantial breakfast eaten in the gray dawn of the morning, we were ready for the start. It had been decided that with the present favoring wind It would be better to enter the moose grounds farther to the west than we did on our previous hunt, therefore we struck into an old Indian trail leading northwest and followed it until we came to where it Intersected with the next section line west of the camp; then, leaving the Indian trail, we followed north on the section line, as we had done before on the one a mile east.

I was riding the little mare and carrying my rifle across the saddle ’horn, while the Trapper, having stuck his gun into the holster which hung at the side of my saddle— to relieve himself of the Incumbrance— walked behind in the trail broken through the tall grass and pea vines by my horse.

We had progressed in this way for a short distance, laughing and talking without a thought of moose so close to camp, and had just climbed a short, steep slope leading to a flat bench above, when there was a furious commotion in the brush at the right of the trail, and before the Trapper, who had fallen behind, could reach me and extricate his rifle from the holster and before I could get a shell Into my empty gun, a large bull moose, with an Immense spread of antlers, dashed across the section line In front of us and disappeared In the timber, while his mate, a fine cow, made off with the speed of an express train In the opposite direction.

The Trapper glared at me in a vindictive way, and I looked at him the same. Then, addressing his words to no one in particular, he sputtered out a string of blueish colored words which might have been "Blankety blank the blanked billy be dad busted blank blanked dad busted blank to stagnation and back again, who didn't have sense enough to carry a gun when we went hunting.”

After a pause ho asked: “Why the blank didn't you shoot?" I told him and a silence settled upon us as we moved on again, crowding soft-nose shells into the magazine of our rifle as we went. After crossing the little creek about a half mile west of where we started our first moose on the previous hunt, the Trapper left me and took a course northwest, along the west slope of the ridge, telling me to continue on for a half mile until I came to where the section lines Intersected and then tie my horse and strike through the brush, keeping as straight a northwest course as possible, until I came to another section line, when I could return without difficulty or danger of getting lost.

You can download the original photocopy here:

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Bartlett William C Hunting and Camping in the Alberta Wilderness 5 1910 Searchable.pdf | 414.6 KB |