SEVERAL years ago a story I read In one of the leading magazines, descriptive of the Canadian West and the great and almost unknown game-infested wilderness laying north of the Saskatchewan River, awakened in me a longing to visit this primitive land, to see for myself the vast reaches of undulating prairie and brush land, and to follow the old Indian trails leading north, Past crystal lakes, and over rushing streams with quaint tragedy suggesting Indian names, until the last sign of civilization was left far behind and our own new-made trail would be the only one to follow back.

This, I suppose, was the "wanderlust," or the "call of the wild," of the primitive man in me. But, whatever it was, it grew on me, day by day, until at last I mentioned it to my friend Bill, and his friend the Professor, and proposed that we cut all other engagements and go.

Bill and the Professor were delighted. They declared it was just what they had been thinking about for the last six months, and that they would be ready to start in a week. That night we met in my friends' cozy bachelor quarters and outlined our plans, discussed and decided upon the guns, ammunition, and other paraphernalia required for the trip, and the next day set to work getting the outfit together. The end of the week found us aboard the west-bound train out of Parkersburg, West Virginia, and on the way to the big land away to the northwest, the land of the "Chinook” and big game.

Our first night camp was in Columbus, Ohio, our second in Detroit, and the third found us aboard a swift lake steamer bound for Port Arthur, Ontario; there we transferred to a train over the Canadian Northern, and at 2 o'clock in the morning, eight days since leaving home, we unloaded ourselves and baggage onto the station platform at Vermillion, a little mushroom town in the province of Alberta, Canada.

The morning following our arrival in Vermillion, we repaired to the town livery stable and there procured the services of a driver—who was also a guide—a team of bronchos and a light spring wagon were then secured, in which we made a preliminary excursion into the “Hog-back,” a strip of hilly wooded country to the north, bordering the south bank of the Saskatchewan River. We returned the following day, as we found that game and fish were scarce on the south side of the river; the game having been frightened out by the encroaching settlers, while the fish it seemed had never existed: why, I will explain later.

It was long after the sun had set when we again drove into Vermillion. We had covered seventy miles in the two days' drive, over a trail so new that at times it was hardly to be distinguished from the untrod prairie, which it traversed. On the way back we made our plans for the future, the main feature of which was a two weeks’ trip into the Moose Mountains, bordering on Long Lake and situated about seventy-five miles due north. In this region (|t was reported) big game, such as moose, elk, deer, bear, wolf and lynx were plentiful, and the fishing unexcelled. The report of fish was one thing that decided us on Long Lake. For, since our arrival In the district, we had not even sighted a minnow, a surprising fact considering the thousands of beautiful fresh-water lakes that dot the whole country, from one of which a fish had never been taken.

At Darling’s ranch, where we had taken dinner the day before, we were informed that it was on account of a small water bug which swarms in all the lakes and streams of the region, making them untenable for the fish; but I was of the opinion that it was due to the thousands of water fowl, which make these waters their home, and have devoured the spawn and young of the fish, until they have become extinct I found proof of the correctness of my surmise in the fact that north of the Saskatchewan, in the mountainous regions where the lakes are generally surrounded by high hills, the ducks were comparatively scarce, while gold eye, pickerel and white fish were plentiful.

We were up bright and early the next morning and, after breakfast, repaired to the Western Canada Trading Company’s store. We had made out a list of provisions for a protracted stay in camp, so we were not long in getting together and packing our outfit on and around the same familiar “Democrat” in which we had been riding for the last two days.

Our food supplies consisted of sugar, coffee, flour, bacon, candles, a few’ potatoes and onions, soap, condensed cream and several absolutely necessary edibles. Our cooking equipment Included a large frying pan, or skillet, a coffee pot, several buckets, a boiling pot, spoons, knives and forks, pie pans for plates, tin cups for coffee, and a small two-hole sheet iron camp stove. We also purchased several heavy blankets and such heavy wearing apparel as we would need If cold weather caught us. A heavy wall tent completed the outfit. Our old driver of the two preceding days was on the box, or rather, on a huge pile of coats and blankets, which, for lack of room, had been piled on to his seat Then, everything being ready, with each of us perched some place on the load, we were off for the moose country, followed by the best wishes of a good part of the town population, assembled to see the "Yankees” off.

Driving north to the edge of town, we crossed the Vermillion River by way of a substantial new bridge; then swung northwest over the old "half breed” trail, which leads through forty-five miles of the most beautiful country the world can produce, to the government ferry over the Saskatchewan.

The day was Ideal. The sun was shining bright and warm out of a cloudless sapphire sky—as only an Alberta sun can shine—and flooding with a golden yellow light, the wide reaches of undulating prairie land that billowed away ahead, and melted into purple mauve where the low distant divide merged in the sky above Scores of yellow- breasted meadow larks rose from the trail side; as we passed the wayside thickets the robin red-breast darted out in jerky flight, and the native whiskeyjack rose from saskatoon and poplar, and, light as wind blown thistledown seemed to float away to neighboring brush or coppice. Everyone was in good spirits, and lounged back in satisfied ease, coatless, and with the inevitable pipe going, while the Professor in giving vent to his exuberance, roared out what seemed to the rest of us an extempore medley of disconnected notes, but which he declared to be a correct rendition of “Dreaming."

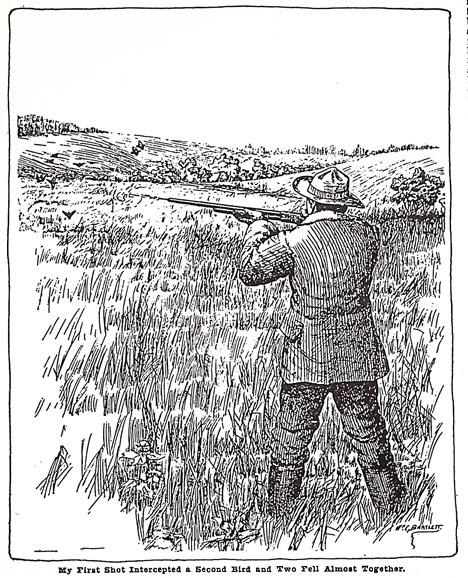

Grouse was wanted for supper, so each of us kept his eyes busy looking for them, along the way, Bill and the Professor even getting out and beating the grass covers on either side as we drove along. At last, after we were about fifteen miles out. I discovered a flock sitting In the grass about forty yards to the left of the trail; nothing but their heads was visible and it was only my early experience, gained in shooting prairie chicken, that enabled me to distinguish them from the dry weed stalks which surrounded them. Knowing that the Professor would go banging away with his rifle if he knew they were there, I quietly requested the driver to stop the wagon: then getting out, walked up and flushed the covey. My first' shot intercepted a second bird and two fell almost together. My second was a clean kill, and my third bird wheeled at the shot, flew a short distance at right angles to its first course and fell dead in a small thicket of poplar brush. That was all we needed one apiece for supper—so I gathered them up and walked back to the wagon. The Professor was very much hurt because I had not let him shoot their heads off with the rifle. I agreed with him that the birds would not have been shot up so badly had I known and been more considerate of his wishes. Remarkable as it may seem at this late date, every now and then we passed the white bleached skull of a buffalo—one of the relics that comprises all that remains of the mighty herds which once roamed the surrounding prairie; one, sticking on the end of a pole, placed there by some passing traveler, ad the outside shell of one horn still clinging to the core, while others lay as perhaps they had for the last thirty years, staring through eyeless sockets at the passer-by, a silent reminder of the cruelest slaughter and grimmest tragedy that the Western plains have ever known.

Here was the favorite winter range of the buffalo In the years gone by. Here they were plentiful, and here they made their last fight for existence against the remorseless horde of white destroyers who relentlessly followed and shot them down until the last woolly brown coat had been stripped off. And the carcass left as it lay, to be torn to pieces and devoured by the wolves, and only the bare bones left to work the scene of tragedy: the stripped skull gleaming white through the yellow buffalo grass, like marble marking a fallen monarch's grave.

Old George Atkinson, a Scotch half breed who was later employed by myself and others to guide us on a subsequent trip, told me that he had been employed as a buffalo killer, by a party of whites, when buffalo were plentiful—thirty-five years before—he said) that he had killed hundreds of them in the Vermillion Valley. The method employed was to ride up with the herd—a very easy matter when mounted on a fairly good horse—and then shoot them down as fast as he could load and fire. The point selected for the shot was the hollow depression just in front of the hip bone; tin- bullet ranging diagonally forward and downward. and generally killing instantly. After the "Killers" came the "Skinners" with wagons. and the hides were stripped off and piled into the wagons until a load was secured, or there were no more buffalo to kill. Ami still you hear people contend that it was the Indian who destroyed the buffalo. Worse still, one writer claims that the gray wolf was responsible for his extermination, a statement which anyone who has traveled the old buffalo trails and talked to the active principals in his destruction, cannot help but brand as foolishly absurd. It was the unprincipled white man and his greed for the dollars the hides would bring, and the passive Indifference of a government which should have stopped the slaughter that was responsible for this crime.

As night was approaching wo kept a lookout for a place to camp, where water and fuel would be easily accessible and plentiful. Coming out at least onto the edge of a low terrace like line of bluffs which marked the termination of a wide meadowlike valley, we decided to cross to the opposite side where on a low hill, nestled a small white walled cabin with surrounding corrals and out buildings, and make it the scene of our first night camp.

Descending into the valley we crossed a small creek in which the Mallards were holding some kind of a convention. Here Hill. gun in hand, slipped over the tail gate of the wagon to try for a potshot and the rest of us drove on up the hill, and selecting a nice smooth spot, back of the corral, proceeded to make camp and prepare supper.

After bringing water, the Professor tackled the pitching of the tent, while I began operations on my grouse, and by the time Bill got in with his duck story the tent was up and my grouse—nice young ones—were broiling over a fine fire of live coals: the coffee was set to boil over another fire, the

kettle hanging from the end of an inclined stake, Indian style, and several slices of bacon were put to fry in our big camp skillet: a can of condensed cream was opened, and the bread—we had brought several loaves—cut in generous slices. Then, the driver having finished caring for the horses and rejoined us. each man was given a pie pan, tin cup, knife, fork and spoon, and the announcement made "Supper’s ready."

There are some who read this who have always lived in the East, where the sullen roar of civilization eternally drowns the voice of nature. There are some who travel: but always where the repulsive dust and smoke, cast up by the world's tramping millions, assail the nostrils like air from a foul tunnel and the works of man have forever hidden from view, or destroyed entirely, tin: beauties of the natural world as it was. It is difficult to make one of either of these two classes understand what fine- words those are—"Supper's ready"—when uttered under the above conditions. There are some of you who sit humped up over a pile of letters dictating to your stenographers, or poring over a ledger, with big dollars always before your eyes. Of course, you can't understand; but then- are others who have beard the words spoken by a man standing in the red glare of a campfire, a huge broiler of smoking grouse in one hand, a steaming coffee pot in the other, a blue sky with pale stars just beginning to appear overhead, and gradually verging into orange in the West, where the sun, like a great globe of crimson fire, has just set: a soft breeze, scented with the peculiar, delightful odor of lake and prairie, blowing always from the opposite side of the fire, and around him the mysterious sounds of the wilderness; the chuckling of ducks as they pass overhead on whistling wing: the call of the loon, weird mid uncanny, echoed from a faintly gleaming, distant lake, and the troubled whimper and wail of a lonely coyote sounding out where the prairie rises in purple black outline to meet the darkening sky. Under these conditions, with a healthy appetite, and trouble thrown to the winds, those who love experience, will agree with me that these two words are among the

Everybody set to: Grouse, bread, bean coffee, and <-v<-u the bacon disappeared as by magic, and when it was all over I knew that there were no invalids in the outfit. Just as we finished and were lighting our pipes, a coyote, stationed on a near hill began his serenade—an old-time joke of h on the tenderfoot. The Professor leaped to his feet and yelled for us to listen to the pack (?) of wolves. The animal evident! heard him and redoubled his efforts: now giving a close imitation of a general dog fight, then changing to cats, and winding up with a grand climax of dogs and cat together, in mortal combat. The Professor in the meantime, became wildly excited. It was the first coyote he had ever heard.

One of the most, if not the most pleasant features of a night camp is the period c peaceful repose, which follows the evening meal: after the crude dishes are washed and cleared away, when the pipes have been filled and lighted with glowing brand from out the blazing campfire, that has been pile high with fuel previously cut for the purpose.

Then It Is that one feels at perfect peace with the world and all mankind and stretched out at ease on the windward side of the warm blaze we contentedly puff away on corn-cob or briar and tell the tales c times gone by. or sing the old songs with the easy tenor and bass that all know, while the firelight flickers and flares in the gentle night breeze, and dimly, lights a vague circle of the campfire right through which the trunks of a near-by birch thicket loom dim and undefined, like a row of waiting ghosts. Then it Is that you talk and grow silent watching the fire burn lower and lower, and you look across at the other boys and they too are quiet, and nod, nodding lower, and lower, like the fire, and it is bedtime.

Thus, it was that Bill, the Professor, the guide and myself passed our first evening In camp.

Early In the evening the old half-breed, who lived in the white walled cabin I have previously mentioned, came over and paid us a visit lasting well Into the night We learned from him that It was twenty miles yet, before we came to the river. He was a very nice looking fellow, well dressed, but wearing the Inevitable wide, stiff-brimmed gray hat and beaded moccasins. He told us that he owned IGO acres of land, 150 head of cattle, and about fifty horses; therefore, by allowing a fair average for livestock and acres, and then doing a little skilled estimating, one can soon come to the conclusion that Pat LaVeal, as this breed was known, was fairly well off.

Bill had cut a lot of long grass from a neighboring lake side, and, having piled it in the tent, he spread our blankets and robes out with the hay beneath, and our bed was ready; whereupon, we turned In, to sleep like cubs in February, until the soft robe flush in the East spreading upward and outward and flooding the moist, drowsy landscape with a soft light proclaimed the dawn of another day.

You can download the original photocopy below:

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Bartlett William C Hunting and Camping in the Alberta Wilderness 1 1910 Searchable.pdf | 1.58 MB |